The gravestone and its location in a well-kept cemetery is sometimes the beginning point for tracing one’s own family history. It is frequently a starting point for learning about our ancestors’ lives and leads to the more essential teachings and experiences they intended for us to discover and understand.

The physical body may or may not be present, but cemeteries and individual memorial stones may be a goldmine of information.

Even when a person dies, they require a means of identification to distinguish them from the other people buried at the cemetery. Memorials and headstones assist people in recognizing the departed, whether for family members, friends, or society.

People put a lot of attention into a loved one’s gravestone because they want to make something handcrafted that honors their loved ones. One reason people choose gravestones (like the ones available here) rather than actual flowers for memorials is that stones endure eternally.

Did you know that headstones may be used both for burial and cremation? That wasn’t always the case, particularly across cultures. In Christian and Jewish religions, for example, monuments were historically connected with burial.

When it comes to the Jewish faith, have you ever pondered how Jewish tombstones from the Middle Ages ended up in an Italian monument? Let’s find out.

Jewish History in Italy

Jews have lived on the Italian peninsula for more than 2,000 years. Even before the Temple of Jerusalem was destructed, there were Jews living in the city and the southern provinces, where they had come as traders and refugees. The temple was the center of Judaism at the time.

It might seem like the history of Jewish life in Italy is just one long story of pain and trauma: slavery by the Romans, the Inquisition and persecution by the Church, and being forced to live in small neighborhoods during the Middle Ages.

In 1516, the first of many ghettos was set up in Venice. Since the Middle Ages, there has been a Jewish community in Ferrara. It was especially strong in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the Este dynasty, which ruled the Emilia-Romagna city, refused to put Jews in a ghetto, even though other Italian cities were doing so.

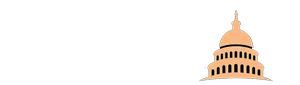

For 500 years, various columns stood tall in front of the court of the Ducal in Ferrara, situated in Italy. The unique bichrome column on the left featured a picture of Borso D’Este, Duke of Ferrara, while the tiny Arch of Titus atop an equestrian Marquis Niccol III can be found on the right (1413-1471).

He and his immediate successors made Ferrara a shelter for Jews, particularly those banished from Spain and refugees from the Inquisition in Italian regions to the south. When the Papal States took possession of Ferrara in 1598, the Jewish community prospered under the House of Este.

Shortly after, the Jewish badge was introduced, and Ferrarese Jews who had previously lived and worked throughout the city found themselves confined to yet another Ghetto.

The Volto del Cavallo is in the lower right of the 15th-century Palace of Ferrara, flanked by the columns of Borso d’Este and Marquis Niccol III.

The Mismatched Aesthetics

In 1960, significant repairs were needed on the city of Ferrara’s signature: the weird, misaligned columns. Workers on the d’Este column painstakingly mapped out the concentric grey stone rings that ran the length of the column so that they could be removed from the structure.

They couldn’t believe what they found when they tore down the column. Freed from the column, the stones revealed themselves to be Jewish grave markers inscribed in Hebrew.

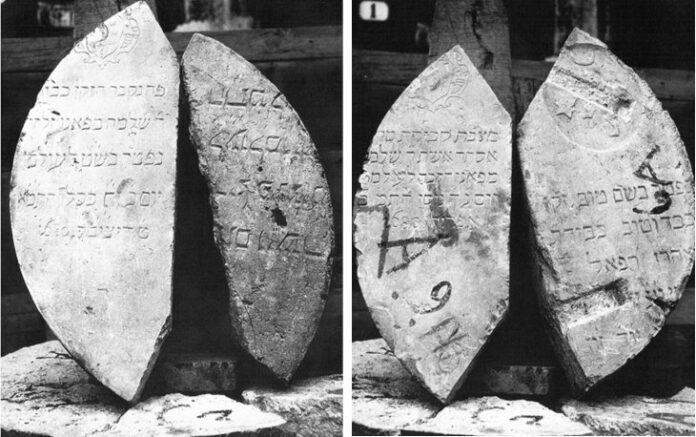

It took 36 shards of desecrated tombstones to be cut up and molded into the proper shape to meet the specifications of the column. The inscriptions were identified by scholars as having been written by members of the Jewish community in Ferrara who had passed away between the years 1577 and 1690. These individuals included Rabbi Shlomo of Fano and his wife Esther, who both passed away in 1680 within a few short months of one another.

On a practical level, the grave markers were painstakingly sized and prepared, quarried for their strength, longevity, and beauty. They would have constituted a major, albeit heinous, shortcut for the builders if they had been removed from their original sacred locations.

The Never-Ending Mystery

The “how” issue, on the other hand, remains a mystery to this day. The column was built in the 1450s and stood for nearly 200 years before being severely damaged by fire on December 23, 1716.

According to Nicol Baruffaldi, a medieval historian, Marquis Francesco Sacrati obtained the stones from Jewish graveyards by “paying in full for their value to the Masters of the Ghetto.”

It is exceedingly doubtful that the Jewish community would have gladly relinquished their relatives’ gravestones, especially given that many of the graves belonged to persons the Ferrarese Jews would have known – grandparents and even parents of the generation alive at the time.

Ferrara’s community record book, or Pinkas, for that era, is sadly destroyed, but records from a few years later reveal a great debate centered on the usage of tombstones for repairs related to flooding caused by the Po river. Many rightly alleged that they were unjustly taken from the Sephardic population of Ferrara, while their owners insisted that they had been duly purchased and paid for.

The gravestones were photographed during the 1960-61 repair, preserving the historical record. Surprisingly, they were not restored to the Jewish community but were instead relegated to the column, where they remain to this day.

To protect the column against earthquakes, a reinforced concrete core was poured in the middle of the column, and this necessitated additional destruction of the column’s historic outer walls. Pope Pius V accused the Este family, who had always protected Jews, of a disastrous earthquake that struck Ferrara in 1570.

The Fate Of Jewish Communities

Younger historians like Dr. Antonio Spagnuolo of the University of Bologna, who is looking into what happened to the missing tombstones from the Jewish community in Ferrara, have been tasked with reconstructing this horrible past.

His research has concentrated on essential sources such as the Community Archives, which are currently housed in the National Library of Israel, but he observes that the Jewish community’s silence when the stones were found in 1960 adds to the mystery.

With scant papers describing the specifics of the restoration work, it is likely that the small post-war Jewish population of Ferrara was either unaware of their presence or lacked the resources to adequately complain.

As a result, the gravestones are still entombed today, not in a religious location but in a magnificent column dedicated to the remembrance of an Italian Duke.

However, the tragic narrative is not without historical and lyrical irony. The Duke Borso D’Este had nothing to do with the tombstone vandalism. His statue was built 250 years before the markers were utilized to buttress the column. On the contrary, the House of Este was well-known for its extraordinary record of kindness to the Jewish minority.

Nearly 600 years later, the Ferrarese Jewish community continues to honor his memory with the stones of their forefathers supporting the Volto del Cavallo’s magnificent column.